Spring 1978

Nineteen thirty-seven was a year of upheaval for your grandfather and me, Pauly.

For nearly a decade, we’d been living this strange life. We’d grown used to it, but it wasn’t stable. It was a constant balancing act. Stealing time together, keeping our relationship secret, hoping for the best.

Never let yourself get into that sort of situation, if you can help it.

Lying and hiding hurts everyone. It hurts the person being lied to – and it takes a toll on the liar too. It puts a strain on your friendships, if your friends have to cover for you – or if they refuse to. It distorts your character, and it can make you ill.

Make no mistake: I was still having a lovely time in beautiful, leafy Hampstead, living with charming, wealthy people, living the life of an intellectual and having adventures in the City in the company of an exciting man.

On the other hand, I saw myself getting older, with no security and no real hope for the future. I was thirty-five, about to become thirty-six, and I had no house, no husband, no children and no career. I was just working for friends as a glorified childminder, a job for which I had no qualifications at all, and I was going out with another woman’s husband.

I was glad, in a way, when change was forced upon me. I don’t know I’d have had the strength by myself.

Charmian had turned fifteen, and Robert and Esther had a long discussion about her future, in which they involved me. We all agreed she wasn’t fulfilling her potential at her London school: it wasn’t stretching her academically, and she was a bright girl. They decided to send her abroad to complete her schooling. To a boarding school in Lausanne, Switzerland.

That meant my role was at an end, after nearly seven years looking after her. It was quite a wrench for both of us: we’d grown very fond of each other.

On the practical side, I needed to find a new job – and a new place to live. The Lennoxes said I would have a home with them for as long as I wanted it, but I didn’t feel I could impose on their hospitality.

They’d been very good to me, but I needed to stand on my own two feet, not live on someone else’s charity as a ‘poor spinster’.

Percy, meanwhile, was planning a career change – another one. At the age of forty-nine, he’d grown dissatisfied with the law, the hobnobbing with solicitors and barristers, the petty politics.

‘I’m sick to the heart with it,’ he said one evening after dinner at the Lennoxes’. ‘It’s just like the blasted RAF, all the kowtowing to jumped-up fools. Present company excepted of course, Robert.’

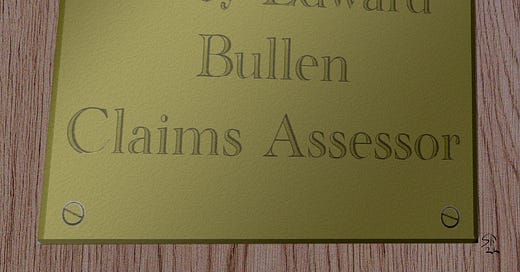

He was going to set himself up as an insurance claims investigator and assessor, he announced. It would be fun and lucrative: he’d specialise in motor insurance claims, combining his love of motoring and all things mechanical with his knowledge of insurance law.

Robert, Esther and I thought he was just letting off steam, Pauly. We thought it was pie-in-the-sky talk.

He was serious, though.

He rented rooms in Southampton Buildings, on Chancery Lane – and he asked me to come and work for him. And live with him as his wife.

I pointed out that he already had one of those.

Getting a divorce isn’t easy, you see, Pauly. A very good reason not to rush into marriage, young man. ‘Marry in haste, repent at your leisure,’ as they say.

Do you know, until the 1920s, only the husband could file for divorce? Ridiculous.

Now, since the 1923 Act, both parties could, but only on the grounds of adultery. This meant that divorce almost inevitably involved scandal and potential loss of social status. People were very prim and proper in those days – or they liked everyone to think so! Behind closed doors, it was another story. Oh yes.

Human beings are such hypocrites.

Public opinion wasn’t something a person of the professional classes could just ignore or laugh off. Your colleagues and business contacts, even your family, might shun you, cut you off, if your name was associated with a messy divorce case. It might mean the end of your career and your social life.

Percy told me a new law was coming in. Additional grounds for divorce would now include cruelty, desertion and incurable insanity.

‘That hardly helps matters,’ I thought.

In the midst of all these discussions, Charlie came to visit me.

It was a shock, I can tell you. We’d barely exchanged more than a few meaningless sentences over the past eight years. Now here she was, wanting to talk to her husband’s mistress. I thought she might throw a fit, attack me verbally or even physically.

Nothing of the sort. I have to give it to her: she was very calm and dignified. I couldn’t help but respect her for it.

She knew perfectly well what was going on, she said. Had done for years, ever since I’d moved in with the Lennoxes, but she’d expected Percy would get tired of me. Like the other girlfriends before me.

She wasn’t going to give Percy a divorce.

Never, as long as they both lived. As far as she was concerned, marriage was for life. Percy had asked her to marry him when he was a young clerk in her father’s office. She was four years older than him, and it’d been love at first sight, she said.

Or it had for her, anyway. There was an advantage in marrying the boss’s daughter, she hinted, for a young clerk with nothing but raw ambition.

At the same time, she knew there was no point in trying to keep him, or stirring up a scandal which would hurt her, George and Daphne as much as it would Percy and me.

So she was going to let him move out, and Percy and I could get up to whatever games we liked.

But I would never be Mrs Percy Bullen. I would never have a ring on my finger, and when, one day, hopefully not for many years, Percy died, she was going to make damned sure I never got a penny in inheritance.

Think twice about taking on a solicitor’s daughter, she warned.

‘And be wary of Percy taking advantage. He’s very charming, but he’s a selfish man. He doesn’t mean to be, but that’s his nature. He uses people. Don’t let him turn you into his unpaid skivvy, Lizzy May Batt.’

And those are the last words she ever said to me. It was food for thought, Pauly, I can tell you.

Your grandfather was a wonderful man: talented and hard-working, generous and kind, and a dedicated father to your Dad. There were times, though, when I remembered Charlie’s words and thought to myself: ‘Hmm.’

Then, in early December, I remember it was a frosty morning, my brother Ernie came to see me. We hadn’t seen each other in many years; he had a thick beard and had put on weight. I almost didn’t recognise him.

He told me that Mother was dying, and I was to come with him and see her. Right now.

I said no.

My mother had never shown me an ounce of affection as a child, and she’d played no part in my life since I’d turned twenty-one and walked out of hers. We had nothing to say to each other.

She died that night.

I didn’t go to the funeral.

It would have been hypocritical, you see. I wasn’t sorry, and I wasn’t going to pretend I was. I wasn’t glad either. I just felt nothing about the death of this strange woman who’d given birth to me, but never treated me like a daughter.

I wrote to Father, tried to explain, but I doubt he understood.

Coming up:

This Friday in Tales from the Wood: A new love enters Pauly’s life, and he prepares to receive a visitor from abroad. (Paid subscriptions.)

Next Tuesday in Lizzy May: Lizzy May leaves Hampstead for Holborn, and finds the high life more stressful than she imagined.

"That hardly helps matters." lol. I'm loving this. Well done.

Got chills reading that part about her mother's death. No sugar-coating.

"I wasn't sorry, and I wasn't going to pretend I was."

I love how real this feels. It's not polished "proper society" stuff. It's just humans trying to grab some happiness while juggling everyone else's rules and expectations.

Thank you for writing Steve.

I hope you are having a good week.