Summer 1981

Hello Pauly! You’re looking well – quite a tan. It suits you. The weather must have been good in Germany. Did you have a nice time?

In the end? Well, that’s the main thing, I suppose. It’s good when things work out well in the end. Sometimes the difficulties along the way make us appreciate our good fortune even more.

Sometimes.

This might be a good time to finish our story, don’t you think? Although perhaps ‘finish’ isn’t quite the right word. Because I’m still here, after all. Nothing really ends.

I’ve been putting it off, telling you about your grandfather’s illness. It’s still difficult for me to talk about this.

Well, let’s see. It was in the mid-fifties, when Christopher was in his teens. He would have been thirteen, I think. Yes.

Percy had a coughing fit in the garden, and when he looked in his handkerchief, there was blood. Quite a lot of it.

This was after months of general ill-health that he’d brushed off as being ‘a bit under the weather.’

Even he had to admit that something was wrong now. He went to see our family doctor.

Dr Goddard – who was just a young chap back then, fresh out of medical school – sent him for X-rays and tests. It wasn’t long before the results came back. It was bad news. The worst.

He had lung cancer.

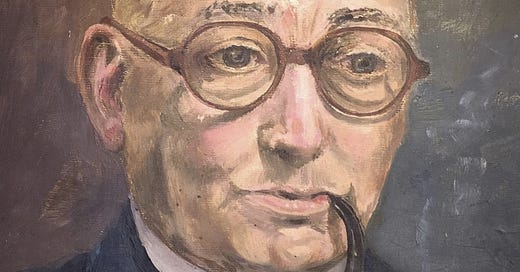

It would have been the decades of pipe smoking, you see. He’d smoked ever since he was conscripted into the Royal Naval Air Service, in the Great War. All the young men did.

It was that blessed pipe that brought us together in the first place, in a way. Do you remember how we met? The cross words we had in the concert at St Martin’s, all that time ago?

At first it was believed that pipe smoking wasn’t as dangerous as cigarettes, because tobacco smoke wasn’t inhaled deeply through a pipe. That turned out not to be true, though.

By the fifties, we’d known about the risks for a long time, mind you. Even though the tobacco industry tried to cover them up.

He just couldn’t kick the habit. Anyway, he never believed that bad things would happen to him, or us. Anything that worried him, he would just brush aside. Your Dad reminds me so much of him, sometimes. He smokes too much, too.

They rushed Percy to see an oncologist. More tests.

We were told that he had a slim chance of surviving, if he was operated on immediately. If not, he had no more than a year to live.

He decided to take the year.

‘Better a bird in the hand, old girl.’

In the end, he held on for two. As I said, he was a strong man.

As I’m sure you can imagine, the diagnosis threw us into a panic. What could we do? How could we tell our son? What would happen to Christopher and me? Was there really no hope?

All these things were going around and around in our minds. I’d lie awake listening to Percy’s troubled breathing, thinking all these useless thoughts, finding no answers.

On one thing we were united: we had to get married.

What I’m about to tell you, I’ve never told anyone else. I don’t know how much even your Dad knows. It must remain our secret, until I’m dead and gone.

Will you promise me that, Pauly?

Good.

We agreed that we wouldn’t approach Charlie, to beg her for a divorce. She would have refused anyway, and we weren’t going to give her the satisfaction.

We wouldn’t tell Daphne or even George. He was busy with his own life now, married to a nice girl – a German girl actually – and had a baby on the way.

We were going to get married anyway.

That meant that Percy would commit the crime of bigamy. It was a very serious thing, and still is. If the authorities found out, we knew that my Percy could spend his last precious months of life in prison, or be handed a fine which would ruin us.

I could be in trouble too, as an accessory to a crime.

Your grandfather had enough knowledge of the law to believe that we could do it safely, without getting caught. His many friends in the legal profession would help, and protect Christopher and me, after his death.

And so, we made arrangements.

We told Christopher we had to attend the funeral of one of Percy’s old RAF friends. It would be pointless and boring for him to come along. He was happy to stay with Tommy for the weekend.

We made an appointment with the registrar at the Westminster register office, one of the biggest and busiest, most anonymous in London, and booked ourselves into a small hotel nearby in Pimlico.

Our wedding day was a bright autumn day, one of those September days which feels more like summer.

On our marriage certificate, it says: ‘Percy John Bullen, 68 years, bachelor’ and ‘Elizabeth May Batt, 55 years, spinster.’

The address we gave is the one of the hotel.

So there we were: officially, but illegally married. I don’t know how much point there really was, considering the risk we took. It’s just a piece of paper. I don’t recall anyone ever asking to see it.

It wasn’t how I thought I’d get married, when I was a young girl, full of hope.

A bigamous marriage might sound like a fun thing to do, the scandalous escapade of your old Nan, who wasn’t always old and a grandmother, but once an unconventional and independent young woman, who met a charming and unconventional man, a dashing RAF veteran, and with him saw more of life, maybe, than most women of her era.

In fact, though, it was just sad.

We tried to cheer ourselves up with a nice meal and a bottle of expensive wine, but we were both making the best of a bad lot. We contemplated the wreck of our lives, the end of all our hopes and dreams, and we wept.

The waiters and the other diners in the fancy restaurant must have wondered what on Earth was wrong.

Still, in the end I married the man I loved, and that’s more than a lot of women can say.

He was the most interesting, the most exciting men I’ve ever met, Pauly, as well as the most infuriating. We had a wonderful life together and I’ll never regret a moment of it, not until the day I die.

In every meaningful sense, we’d been married for over twenty years, since we’d moved in together, into our little flat in Southampton Buildings, overlooking Chancery Lane and beautiful Lincoln’s Inn.

The rest was merely bureaucracy.

After the wedding, Percy held on for another sixteen months. He died three days after Christmas 1957, at home in his bed, with Christopher and me at his side.

Coming up:

This Friday in Tales from the Wood: It’s 1982, and Pauly is in his first term at Leeds University. (Paid subscriptions.)

Next Tuesday in Lizzy May: Lizzy May writes Pauly a letter. (Final chapter.)

How special to have a painting of your grandfather by your father, Steve.

Two more great chapters. I particularly liked hearing about Fish 😆

Excellent chapter, Mate. But sad …