Spring 1974

Hello, Pauly. I hoped you might come today. Everything alright at home?

Good. Well, sit yourself down. Cup of tea and a biscuit?

Now, where were we? Ah, yes.

Mother and Father came from big families. They both had a gaggle of brothers, sisters and cousins. Father had seven brothers and sisters. Mother had only three, but her father, my grandfather, had eleven. So I had lots of uncles and aunts, cousins – and even nephews and nieces who were older than I was.

It was difficult to keep track of who was who, sometimes.

Father’s relations, the Batts, were mostly in the Lea Valley around Ware, but Mother’s lived on the Essex border, in the valley of the River Stort, around Sawbridgeworth and Sheering.

Both families lived in watery sorts of places with good soil.

They all worked on the land. Farm labourers, gardeners, that sort of thing. The Lea Valley was a big area for greenhouses. Not the little things you see in your neighbours’ back gardens. No, these were great big long buildings.

They used to grow fruit and vegetables for the London markets, you see. That’s how Father came to be a nurseryman, like his father before him: preparing the seed beds, sowing the seeds and bringing on the little seedlings for the market gardens all along the valley.

Green thumbs run in our family. I think maybe you could have one, too, if you put your mind to it.

Sheering, now that was more arable land and pasture. There were watermills on the Stort, and Sawbridgeworth was a busy little place, with the barges going down to London.

What did they carry? Malted barley to the London breweries for one thing. Flour for baking too, from the mills. They’d come back with pigeon poo, and other sorts of manure. Fertiliser, you see. If you want the land to grow food for people, you have to feed it food for plants.

Smelly? Yes, it probably was.

Anyway, the Sheering cousins. The Strackeys.

I stayed with them in the summer holidays. As soon as school was finished, Mother would pack me off – as if I were some kind of burden she was glad to be rid of.

No, Ernie didn’t come with me. He was already working as a shoplad in Powells, a hosier’s. You know, a shop that sells stockings and socks?

No, I suppose not.

Cousin Sam would be waiting for me at Sawbridgeworth station with a horse and cart. It was two or three miles to Sheering, where they all lived. A tied cottage. That means it belonged to the big estate where Uncle Fred worked: it went with the job.

It was a small, cream-painted weatherboard house with a thatched roof. There were three main rooms downstairs and three low-ceilinged attic bedrooms perched up in the eaves, amongst the thatch. With their windows peeping out, I always thought they were like little bird’s nests.

There were five children, with me the sixth, and Uncle Fred and Aunty Smudge, so it was quite a squeeze.

As soon as I was sitting up on the cart next to Sam, off came the smart laced boots. I’d run around barefoot the whole summer, if the weather allowed it. My cousins all wore patched hand-me-downs, and if they had anything on their feet, it was clogs.

I really don’t know how Mother got to be the way she was, coming from that family. Her half-brother, Uncle Fred, was an easy-going sort of a chap, and Aunty Smudge, whose real name was Eleanor but everyone called her Smudge, was a kind, lovely woman.

We ran wild. There was no controlling six children, after all. I was mid-way between Sam, the oldest, who was seventeen on my last visit and a young man already, with his broad shoulders and deep voice, and little Carrie, who was Aunty’s sister’s daughter in fact and only three.

It was the holidays for me, and fun, but country children didn’t really have time off like we did. When they weren’t at school, they had jobs to do around home, so when I say we ‘ran wild’, that doesn’t mean we were allowed to be lazy, oh no. No sitting around with your nose in a book.

There were the chickens and the pig to feed, milk to fetch from the dairy and butter to churn, the kitchen garden to water – which meant filling buckets from the well, none of this turn-on-a-tap-and-point-the-hose business. There was firewood for the boys to chop and stack and for us girls, clothes to wash and darn.

We were allowed to roam when our chores were done, and no questions asked, as long as we were home in time for tea. But we were expected to bring back something useful, whether it was wild greens from the hedgerow or hazelnuts, blackberries and mushrooms from the woods. My cousins all knew which mushrooms were good to eat, and which would kill you stone dead.

Mary was the closest in age to me, she was one year older, and Johnny, he was a bit more than a year younger.

It was the Town Mouse and the Country Mouse. You know the story? Well, what I mean was, we came from different worlds. The Country Mice used to tell me all kinds of stories, to see if I was gullible enough to believe them.

Johnny would show me his wounds where the farmer had shot him for trespassing. I think they were just bramble scratches in fact. Another time, they’d have me running across a field because the bull was going to get me. There was no bull in the field, just a few harmless cows.

I remember peeping out the bedroom window when the church bell struck midnight, hoping to see the Headless Highwayman ride by on his big black horse. Of course I never saw him, but in the morning they’d say: ‘Ooh, did you hear the hooves!?’

I got my own back, though, because they had no idea about the city.

To hear me, you’d think that life in Coningham Mews was very exciting, oh yes. What with Lime Grove film studios just down the road, and the Empire and the Palladium across the road. I used to see Charlie Chaplin on the street almost every day – and Ernie often had to deliver silk stockings to Mary Pickford in her hotel room!

Ah, of course you don’t. She was a star of the silent films, an American actress, very pretty with her hair in curls.

So, anyway, Shepherd’s Bush was very glamorous, the way I described it. In reality I’d never seen either of them, or any other stars for that matter, other than on the posters outside the Palladium.

Other times I’d paint it as a smoggy crime scene straight out of Oliver Twist, with Jack the Ripper thrown in for good measure and bloated corpses floating down the Thames. Which runs nowhere near Shepherd’s Bush, of course.

Oh, that reminds me.

One of the pleasures of summer was swimming in the River Stort. Otherwise, I was only allowed to swim at Hampstead Heath ponds. Until Mother said I was getting too old for it to be ‘proper’ and that was the end of that.

Not that you’d want to swim in the Stort downstream of Sawbridgeworth. By the time it’d flowed through the town, the water was filthy. The maltings and the sawmill, you see, and of course, the sewage from the town went into the river.

It was just what they did.

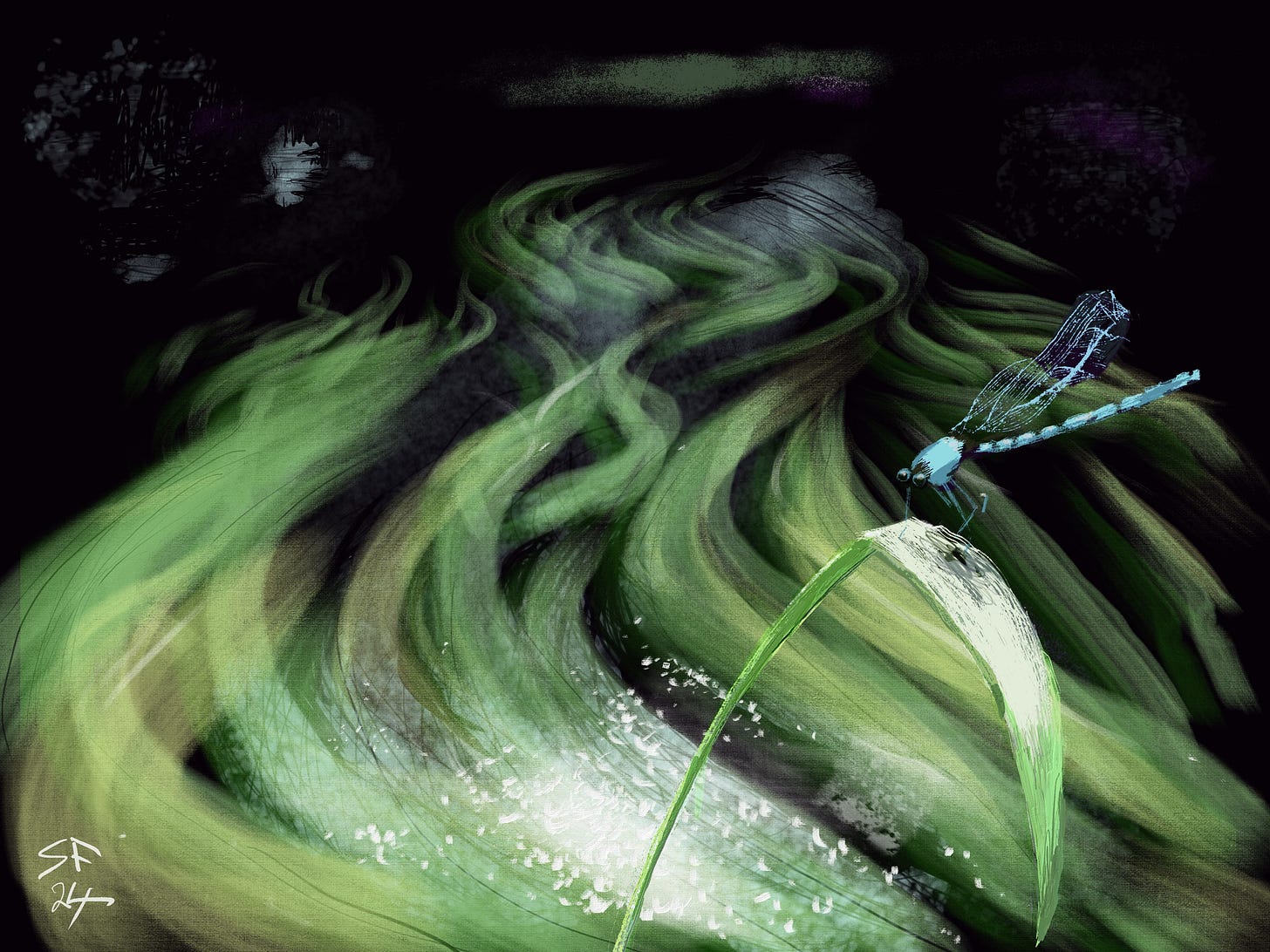

But Sam would take us to a spot above the town where it was still quite clean, with waterlilies and great beds of watercress, and so clear you could see fish on the bottom, their heads pointing into the current and their tails waving.

Then at the end of the holidays I’d have to go home, and Mother would see the stained petticoat, the pinafore torn by thorns, and my sunburned nose, brown farmer’s forearms and the hard skin under my feet. And of course, there would be a big fuss and to-do.

It was the river which put an end to my summers in Sheering. Though I was already home when the awful thing happened.

Johnny and two school friends played truant to go fishing and lark about on the river, as they often did. It was late September and already getting a bit cold that year.

Well, his line got stuck and so he dived in to free it. It was close to a mill race, where the current flowed strongly. They’d been warned not to go in there, but he was a good strong swimmer.

Under he went, and never came up. His friends waited and waited. Then they ran for help.

When the search party dragged the river, they found him. The current had sucked him under and held him there, you see.

After that, Mother and Father decided that there wasn’t enough supervision and Sheering was too dangerous a place for me. Anyway I was eleven by then, and coming to the end of my school days.

Which is another story for another day.

This week in the Friday Novella: Pauly’s sense of humour doesn’t coincide with the Headmaster’s, and what’s up with Mrs Bright?

Next Tuesday’s Tale: Lizzy May falls out with Mother over plans for her future. Meanwhile, Father has a change of job, which brings perks of a musical variety.

Love Pauly & Lizy! And you descriptions & times are vivid. Can not wait to read more

Oh wow, this took me on such a nostalgic journey! The way you paint a picture of the old days—the thatched roofs, the hustle of farm life, and the mischief with cousins—it's like a window into a time most of us will never experience firsthand. Makes me wish we could all slow down and live that simply again, even if just for a while. Looking forward to more of these tales! Hope you are having a good week Steve.