Autumn 1974

I remember the fifth of August 1914 clearly.

It was a beautiful summer’s morning. Mother and I were at home. Father and Ernie had gone off to work as usual, and we had the household chores to look forward to.

Sweeping the floors. Airing the bedding. Washing the laundry. Putting the clean laundry through the mangle to squeeze the water out. Hanging the clean, damp laundry out on the line to dry. Running errands to the shop. Peeling potatoes for dinner. Ironing the clean, dry laundry. Folding the laundry and putting it away. There was always something to do.

Then Mr Smythe next door came round, all flustered and hatless and not his usual dapper self at all. He was a travelling salesman and often away for days, but on this particular sunny Wednesday in early August, he was home.

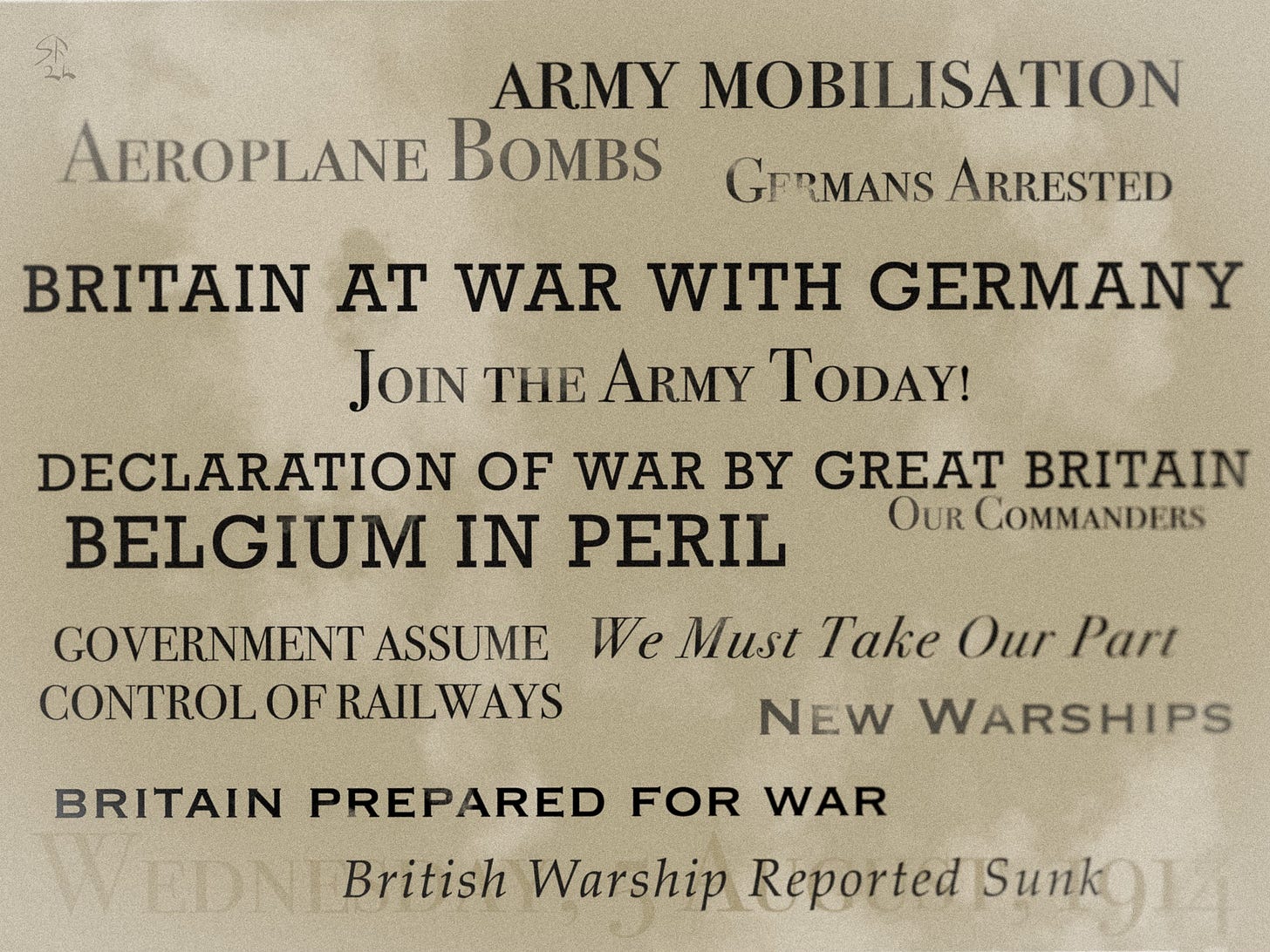

Had we seen the front page of the Morning Post yet?

We shook our heads. I used to read the Post to Mother over our mid-morning cuppa.

No? Well, we were at war with Germany!

The Kaiser had rejected Mr Asquith’s request to respect Belgian neutrality. German troops were already advancing on Brussels! France and Russia were on our side, Austria and the Turks on theirs.

Treaties, you see. Everyone had signed treaties to support everyone else, and so the whole of Europe was drawn into the fight. It had been brewing for months, ever since that Serbian chappy shot the Austrian Archduke, back in June.

Well!

Young men were keen to fight for King and Country, and give the Kaiser what-for.

They thought it would be done by Christmas.

Ernie was twenty-one, and by the time he got home from work that evening, he’d already signed up. His boss had given him the afternoon off to go down the Army Recruitment Office.

He was going to be in the Royal Field Artillery, London Brigade, Fifth Battalion!

He was so proud, my big brother Ernie.

And we were all proud and excited for him, although we were a bit worried too, of course. You know, in case he actually had to go off and fight the Hun.

This was the Territorials, you see. It didn’t mean that he would be sent overseas, not yet. But the Territorial Army, they would stay home in reserve, training and getting ready, in case they were needed to support the professional British Army.

Poor Ernie. He was mortified, when they sent him home, two weeks later.

‘Discharged. Unfit for service.’

His weak chest, you see.

He saw it from a different point of view, later on.

When the letters and telegrams started coming and you could hear the wailing and the sobbing all the way down the street. When the trains came, full of young men missing arms and legs, blinded by mustard gas and their lungs ruined, or shell-shocked out of their minds. Everyone found out then, what war was really like.

‘The Great War’ they called it. ‘The War to End Wars’. Until a generation later, they had another one.

No, this was the summer holidays, when war broke out.

That’s right: I was still at school. Despite what Mother had wanted. She didn’t get her way, for a change.

The authorities were keen for children to stay in school till fourteen, you see. Unless there was a good reason for them to leave early. Well, I wasn’t needed to work on the farm like my country cousins, or to go into service as a scullery maid, or look after younger siblings, or anything like that.

So I stayed on till the summer of 1915. Still no grammar school for me, and no School Certificate, but at least I could carry on with maths, English and French.

Don’t you dare groan, young man.

Those subjects were my ticket out of that house, and into a job where I could pay my own way and have my independence, a room of my own. Somewhere across town, far away from Mother.

I used to read the Girl’s Own Paper every week. It was an illustrated magazine with stories and educational articles for girls and young women. Mother approved because it was started by a religious society, so it was ‘respectable’, but I liked the practical careers advice it sometimes had. And the fashion pages.

I particularly remember this one article about clerical jobs.

The way to a steady job and long-term prospects was the Civil Service, it said. But to get in, you had to be seventeen or over, and sit a stiff entrance exam. That was going to be out of my reach, without a grammar school education.

There were other ways, though.

There were typing schools and secretarial colleges springing up, for the hundreds of thousands of office workers that Britain needed. What’s more, there were bursaries and loans available – for ‘promising, respectable girls’ from working-class families.

Attending day classes or evening school, I could learn to write shorthand and type, keep financial accounts and do filing. Later, maybe I could become a telephone switchboard operator, or work in a telegraph office.

What I really, really wanted, though, was to be a journalist. I loved writing stories and essays, and finding out about things.

That seemed pie-in-the-sky, back then, so I kept it to myself. Although, as we’ll see …

But anyway, there was an address at the bottom of the article. It was for something called the Society for Promoting the Education of Women, or SPEW for short, which led to unkind jokes.

Anyway, I wrote off to this SPEW – being very careful to keep the letter away from Mother, of course. Ernie was in on my secret.

I heard nothing … and heard nothing. So after a while I thought: ‘Well, that’s that, then.’

Then, long after I’d given up, I got a reply. It was May 1915.

I would need a reference from my school and permission from a parent or guardian, the reply said. If the reference was satisfactory, they’d help me find a suitable course. I could enrol and start in the autumn. In just a few months’ time!

My headmistress wrote me a glowing reference. Father gave his permission.

Mother couldn’t say much against it, though she wasn’t happy at all, that I’d gone behind her back. It was clear to everyone I’d earn more as a qualified clerk than as an unskilled kitchen maid or shop assistant, and in those uncertain times, that extra might be important.

The nonsense about the war being ‘over by Christmas’ was long forgotten. It was clear we were in for a long fight, and the flag-waving patriots had piped down. After the first Zeppelin raids on London and the terrible casualties from Flanders.

If the war went on another year, they said, the Government might bring in conscription.

Then the Army might take another look at Ernie, weak chest or not. Maybe even Father would have to go off to war, though he was over forty.

There wasn’t just the safety of the men in our family to consider, although of course that was important. There was also the question of how we would manage financially without them.

Privates in the infantry only got a shilling a day, you see.

Well, as a civilian, Father was getting twelve bob for a day’s work, and Ernie seven. Married soldiers got an allowance for their families, another few shillings, but still, we’d struggle to make ends meet, if they got called up.

Mother and I could end up being the family’s main breadwinners.

Fortunately, with so many men away fighting in the trenches, career prospects for women were looking up. There were all kinds of jobs that female workers could do perfectly well, bosses suddenly discovered. Jobs that only male workers had been good enough for, up to that point.

So, that second September of the War, I started at Fulham Girl Clerks Training School. I was just fourteen years old and the youngest in my class.

Coming up:

This Friday in Tales from the Wood: Pauly is given a big responsibility, and a border dispute erupts. (Paid subscriptions.)

Next Tuesday in Lizzy May: as the War grinds on, Lizzy May makes new friends and views new horizons.

Hi Steve

What a vivid and heartfelt memory you've shared—it's like stepping back in time with you. I could almost hear the clatter of laundry through the mangle, the bustle of the neighborhood, and the unexpected shock in Mr. Smythe's voice. Thank you for bringing us into that world with you, and for sharing the hopes, the fears, and the stubborn resilience that made up those days.

I hope you enjoy the rest of your week.