As she descended the slope, she tried to process what she had just experienced in the forest.

It was qualitatively different to the other two ‘episodes’, as Barry had called them. In both cases, a few months apart, there had been the rushing sensation, the overwhelming of her senses, the loss of balance – but such a specific, vivid vision? No.

Did this mean that she was getting worse? So soon?

‘The disorder presents with widely variable symptoms and its progression in female sufferers is under-researched,’ Barry had explained.

‘Quelle surprise.’

‘Well, it is a lot less common in women, you see …’

It would be easier, in a way, to believe that what she had experienced was real. Horrific though the implications were.

And yet. There had been that surreal, dreamlike quality.

The brap of a chainsaw pierced her reflections. Tom was making a start on the windfallen timber from the last storm.

She knew suddenly, with complete certainty, that she was not going to tell anyone, ever. It had not been real, and she had no desire to be put on antipsychotic meds.

Rien ne c’est passé. Fini.1

As she arrived at the woodshed he smiled and raised a gloved hand, bellowed a greeting. Still wearing his ear protectors, he was deaf to her reply. To his quizzical glance at her muddy knees she replied with one of her famed Gallic shrugs, smiled ruefully as if to say ‘Comme je suis bête!’2

Harris heaved himself up and tottered over to her. She scratched his woolly head. Arthritic and half-blind, the old Airedale was Tom’s constant companion. They really needed a new dog for rodent control, but it didn’t seem fair to foist a rowdy young rival on this old fellow.

He’d been a magnificent terrier in his day. That time he dragged home an adult fox, still very much alive and highly indignant …

We were all magnificent in our day, she reflected, as she trudged over to feed the chooks.

Under the hot stream of the shower, she contemplated the course of her day. After such a bizarre and upsetting start, she felt a need for diversion. She also didn’t want to be around Tom until she’d regained some emotional equilibrium.

She’d get coffee and a pastry in town, then pop into the IGA for the few bits and pieces they needed. Drop by the wholefoods store to check on honey sales. Chores in the veggie patch and orchard could wait until the afternoon.

‘Gone to town,’ she wrote on the notepad. ‘Back for lunch xxx.’

As it happened, the day held diversions enough.

‘Millie! How’re you going?’ called Rita from behind the big, shiny-red Marzocco, as the door of the café swung shut behind her. There were no other patrons this mid-week morning.

Amélie had long since stopped insisting on being called by her real name. It seemed un-Australian to take exception to its cheery butchering. Even though it was a perfectly good name …

‘You’ll have heard the latest, then, about the Homestead.’

Rita Gallinari, you self-important baggage. You know very well that I haven’t ‘heard the latest’.

‘No?’

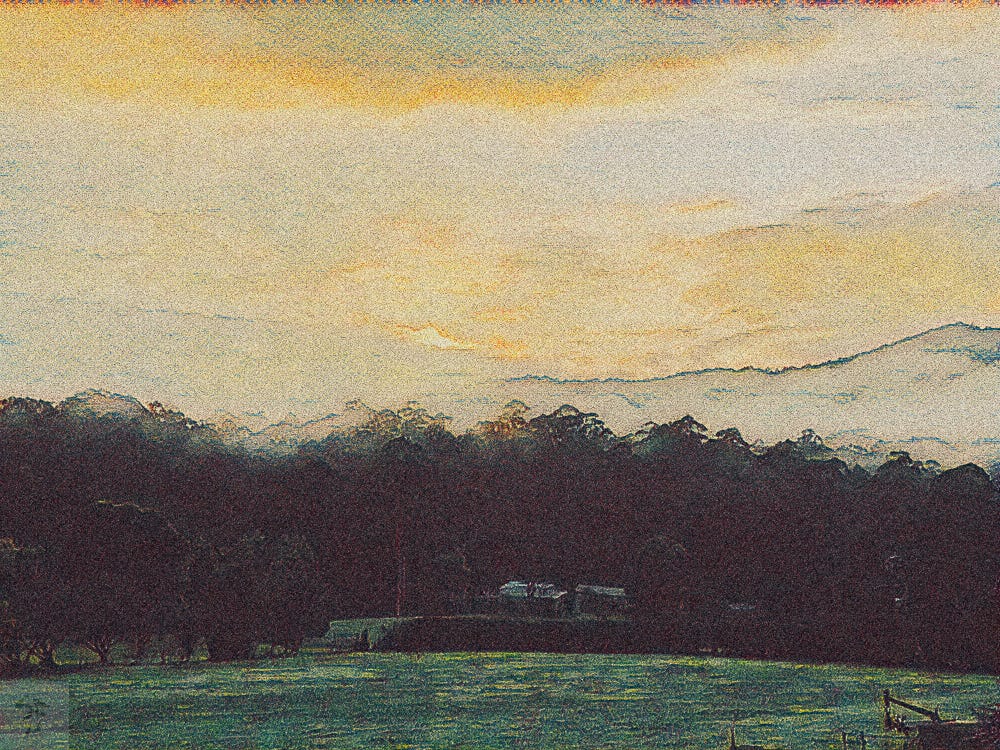

A vexed topic of community association meetings, the Homestead was the earliest surviving building in that part of the valley. A hundred and seventy years old, unoccupied for nearly a decade and crumbling slowly into the hillside. The absence of a heritage listing was baffling.

Tom and Amélie had a particular interest, as the Homestead’s twenty-five hectares of rolling paddocks and mature bushland abutted their property, across the creek.

‘You’re getting new neighbours.’

‘Really? It’s definitely sold, then?’

‘Mm-hmm. Overseas buyer.’

‘Oh, yes?’

I can see you’re dying to tell me more. Come on, lady, out with it.

‘Going to be a conference venue, convention centre, so they say.’

Well, that is news, thought Amélie, as she stirred her macchiato.

Later at home, Tom scoffed. ‘Bloody nonsense. They’d never get planning permission.’

‘Just repeating what Rita said. Singaporean conglomerate.’

‘That woman and her furphies. As if she’d know that.’

‘Her son-in-law does work for Buxtons. Knows what’s going on. You know – real estate grapevine.’

After dinner, they watched TV. One of those tacky home renovation reality shows which had sucked them in.

As usual, Tom got enjoyably outraged at the careless use of power tools and the shoddy work. ‘Will you look at that?’ he snorted, gesticulating at the screen. ‘A bloody disgrace!’ He was referring to dodgy noggins or shonky studs or something.

‘Yes, dreadful,’ she nodded, only interested in the people-watching.

This evening’s episode delivered the goods. There was performative emoting by the female contestants; a meltdown over mis-ordered soft furnishings; tears and hugging of ‘friends’ who would be stabbed in the back by the end of the show. There was equally performative stoic silence among the men as their spouses pouted and whined to camera.

An aerial shot of the site: the camera drone soared and panned to reveal a rutted, muddy paddock. The half-built houses were spiky with scaffolding. Heaps of rubble and dirt lay dotted about. Vehicle tracks scribbled across lush, green grass.

‘I do so hope we’re not going to have all that next door,’ said Tom.

He wasn’t so sure about the planning permission after all, then.

Next week in Telling the Bees:

Chapter 3: Preoccupied

Tom and Amélie broach difficult topics during a walk in the forest.

Disclaimer: The people and events described in this story are entirely the product of the author’s imagination; they bear no intentional resemblance to real-life people and events. The locations are based on real places.

Fr: Nothing happened. Finished.

Fr: How silly I am!

Steve, these story bits are such a fun tease! I can't WAIT for the next episode!!! :D