Spring 1976

Come on in, Pauly. How was your birthday, young man? Twelve years old!

Did you like your presents? Did you get what you hoped for? Good.

Now, where were we? Ah, yes, 1917, and Ernie was finally overseas with the London Irish, sunbathing and riding camels. Having a jolly old time, so he wrote.

It was just before Christmas when the luck ran out for his battalion.1

From what I gathered, they were ordered to take a position in the hills north of Jerusalem, in awful blizzard conditions. In the darkness and the sleet, they ran slap-bang into two fresh divisions of Turkish troops, who were on their way to retake the city.

The British didn’t know the Turks were there, you see. Had no idea.

By the end of the night, the battalion had been wiped out. Nearly six hundred casualties out of seven hundred soldiers. Only one officer left alive of the fourteen who’d started the attack.

The battalion was disbanded, after that. The survivors were shared out between the other battalions.

Ernie missed the fight because he was in hospital in Alexandria. Dysentery, which was a horrible disease caused by drinking infected water.

Maybe he thought he’d let down his pals, by not dying with them on that rocky hillside. I don’t know, because he didn’t talk much about the War afterwards – they never did, the men of my generation.

It wasn’t the thing, to show your emotions.

In a way, he didn’t need to say anything. He came home a different person, even though I don’t think he ever fired a shot in anger, or was shot at. Before he was called up, he was always laughing and joking, had a great sense of fun. A bit of a flirt, he was, which made him popular with his lady customers.

When he came home, he was very quiet and serious. I think he started going to church, which he’d never done before.

Father had a better time of it. His job as a driving instructor kept him well away from the Front. For most of his service – only a year, remember – he was stationed at Salisbury, so he never saw action either.

That’s just as well, because I don’t think he could have borne it, seeing the horses suffer so terribly. They didn’t tell us about that, at the time. Not good for morale.

There was a famous quotation in the papers during the War, about warfare being ‘months of boredom punctuated by moments of terror’. I won’t try to speak for those who’ve actually been to war, but for us on the Home Front, it was true.

And then, in early 1918, the Spanish Flu broke out. It was ‘just’ the flu, but it killed as many people as all the battles and bombs together. Maybe it helped to end the War more quickly, I don’t know. But if it did, it was at a terrible cost.

I remember the victory parades, the music and cheering and flag waving on Armistice Day, and again in July 1919 when the Treaty of Versailles was signed.

Which, with the benefit of hindsight, was setting us up for Hitler and the next war. Ah, but that’s another story and I don’t want to get ahead of myself.

We were glad the fighting was done, of course, particularly as Father and Ernie would be coming home now, but I think we were mostly just tired. And we thought ‘Well, what now?’ The country had been at war so long, it almost seemed we’d forgotten how to be at peace.

Well, by the end of 1919, it was almost difficult to believe it had happened. Almost. Except for the fact that a quarter of a generation of our men were dead or scarred for life, one way or another.

Deary me. I meant to make this more fun for you, what with your birthday and everything!

The trams and buses were running, the streets were brightly lit, and the shops were full of things to buy. A lot of women had given up their jobs and gone back to ‘domestic duties’. Though a lot hadn’t.

Ernie and Father were back in their old lines of work, though they’d changed employers. Father was a packer and porter, Ernie was selling socks and stockings.

I was a ‘lady clerk’ working for London County Council – and much to my annoyance, still living at home.

Oh, but we had a new house.

We hadn’t moved far, just half a mile north to Martindale Road in Wandsworth. It was quite similar to Cambray Road, but the house was older and bigger. We had a formal dining room and a sitting room.

We also had a spare bedroom before long.

Just a few months after being demobbed and coming home, Ernie moved out again.

He’d found a girl, you see. The sister of an Army pal. She was from Norfolk and they had the wedding up there. Then they moved into a flat in Clapham and he continued working in hosiery, as I said.

Her name was Elsie Ruth. And by the end of the year they had a little girl, who they christened Elsie Ivy. We called them ‘the Elsies’.

They had a long life together, Ernest and Elsie Ruth. As far as I know, they were very happy. I say ‘as far as I know’ because things got difficult between my brother and me, later on, I’m afraid. So we lost touch. He didn’t approve of my life choices, so to speak.

It was to do with your grandfather, but we don’t want to get to him yet.

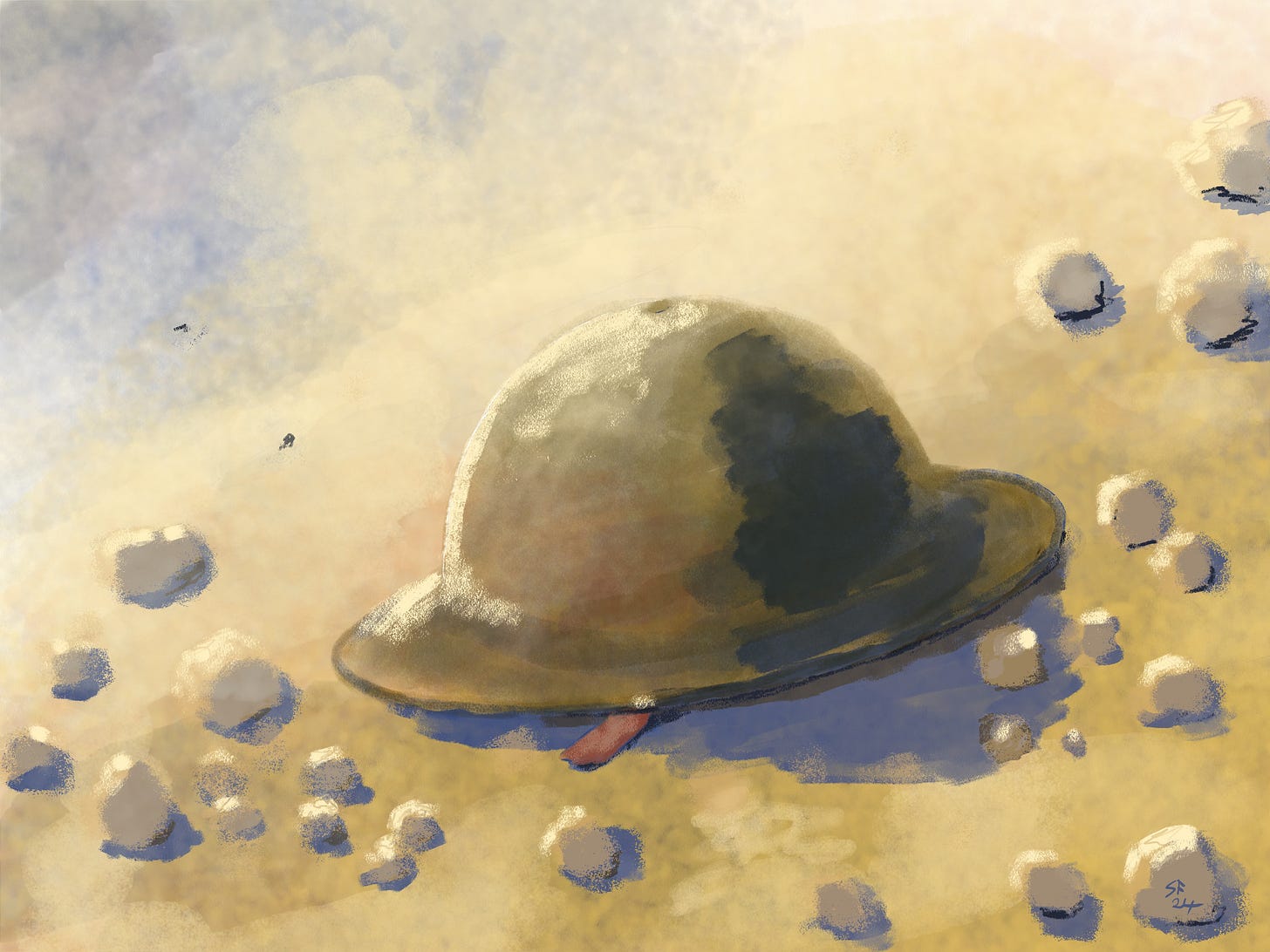

This chapter of Lizzy May is dedicated to the memory of the men of the 2/18th Battalion, London Irish Rifles, who fought in the Great War.

Coming up:

This Friday in Tales from the Wood: Pauly has had enough, and takes matters into his own hands.

Next Tuesday in Lizzy May: Lizzy May makes a clean break and savours single life in the Capital.

The 2/18th Battalion, London Irish Rifles, in the battle for Kherbet Adasseh, on the night of 22–23 December 1917.

A lovely piece Steve.

You'd think we'd learn, wouldn't you. But the world is teetering yet again.

My great grandfather was in the light horse in Egypt. Thankfully, he made it out.

Enjoying the story Steve. Interesting to hear how life was for your Nan xx